Should Hip and Knee Prosthetics Come with a Warranty?

Lately, there have been several articles questioning if hip and knee prosthetics should come with warranties. Considering the current, worldwide repercussions from failing metal on metal hip replacements and modular neck hip replacements, it’s no wonder manufacturers are being called upon to make good. These particular implants have caused major problems for people worldwide and the number of revision surgeries being performed to correct problems associated with these types of implants continues to grow.

However, you can’t look at prosthetic implants the way you would components for a cell phone, computer, kitchen appliance or even a car. Yes, all of these and most other electronics, appliances and tools come with warranties for parts and labor. However, most are limited and you pay extra to extend the coverage should something go wrong. Many warranties also have a list of parts and damages which are not covered even under warranty.

While there is a certain similarity in that everything lasts longer and functions better if you take care of it, you simply cannot compare a prosthetic knee or hip joint with a replacement part for an electronic device or car for which there are numerous models that are essentially the same in design. Prosthetics are not “one size fit all” components made for inanimate objects, but people. The materials used and the process to produce these components is remarkably complicated and even very subtle changes can have dire effects. These prosthetics are implanted into totally unique human bodies of different ages and sizes. People also have varying activity and sports levels as well differences in diseases, or in some cases injuries, that necessitated hip or knee replacement surgery.

As surgeons, we have to trust that the system now in place is working to protect the public from faulty components. As with any product, unfortunately, this is not always the case despite what I believe are good intentions. The FDA is the major government body that approves implants before they can be sold in this country. Manufacturing companies feel the need to constantly offer something new and different in order to maintain and capture new business. Many times, the approval for a new implant is obtained by convincing the FDA that it is similar to another model that already has been approved. This “fast tracts” the approval process. In the past, when a new prosthesis was made, only a small group or beta site would initially use it. These results were studied and reported before the implant would be released to the general population. Unfortunately, this is much less common today.

For the surgical community, peer-reviewed clinical studies and registers are the true test. Many European countries, Australia and New Zealand all have national joint registers which document and follow all of the implanted joints. These registers are powerful tools and have proved invaluable for tracking trends from large populations and more quickly identifying problems. While we have been “late to the party” in creating a joint register here, mainly because of medical legal concerns, mindsets are beginning to shift and a national registry is being rolled out in the U.S.

When patients ask me how long a new hip or knee will last, I tell them I honestly cannot give them an exact number of years because there are so many variables. For example, younger patients, particularly men, not only wear out prosthetic joints faster, but request joint replacements earlier than any other group. In fact, knee replacement surgery alone is projected to increase to nearly one million procedures by 2030

We already know that some hip and knee prosthetics clearly have outperformed others. But it can take 15 to 20 years for implants fully to pass muster. Personally, if I were a patient having a hip or knee replacement, I would be skeptical of the newer implants. My best advice is to have a complete understanding of why your doctor chooses a specified prosthetic and procedure for you, and what his or her success rate has been with that surgery.

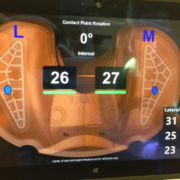

As a surgeon, I prefer to wait until an implant has been tested in the field for at least several years and then I match the proper prosthesis, technique and technology to each individual patient.

Rather than focus on manufacturer warranties, what we as a surgical community need to demand is that “new and improved” prosthetics pass the test of time and are not touted as the best bet because they have been put to the rigors of machines that simulate body forces on an implant, but because they actually have done well in real people.