An Updated Look at the Effectiveness of Hip Arthroscopy: Who is a good candidate?

Arthroscopy is a surgical technique that has revolutionized how some complex problems that develop in certain joints are treated, including the hip, knee, shoulder, ankle, elbow and wrist. For certain diagnoses, an arthroscopic repair is better and easier to perform, with less soft-tissue dissection and much smaller incisions, than performing an “open procedure” surgery to address the problem. Often, the rehabilitation also is faster. In spite of these wonderful gains, arthroscopy (also referred to as a “scope”) is not an appropriate procedure for all problems that develop with these joints.

Knee and shoulder arthroscopies are routinely done, with knee arthroscopy being the most common orthopedic procedure performed in the U.S. Hip arthroscopies are done with much less frequently and by fewer orthopedic surgeons, but also are performed more routinely today than several years ago. Fortunately, new and innovative procedures and instruments continue to be developed for arthroscopic applications throughout the field.

In this blog article, I’ll share my views about which patients I see who seem to do well when treated arthroscopically and those who do not. My practice focuses on helping people solve problems with their hips and knees and although I’m able to help many of my patients by performing knee arthroscopies, I do not perform hip arthroscopies. I recognize that my perspective might be biased because I routinely care for patients with hip problems who have already had hip scopes with poor outcomes. The folks who had hip scopes and were treated successfully don’t make appointments to see me. I also see some patients who I think might be good candidates for hip arthroscopy and refer them to physicians with expertise in performing them.

Some joints, such as knees and shoulders, are generally easier to scope than hips. If you are contemplating a hip scope, carefully choose a surgeon who has expertise with this particular procedure, as with anything, the more one practices the more proficient one becomes.

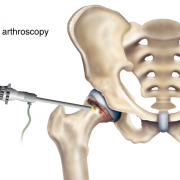

Hip arthroscopy usually is performed through two to four small incisions. Pencil-thin, specialized instruments, including an arthroscope, are inserted into the joint. The arthroscope contains a camera lens which magnifies and illuminates the interior joint structure. This information is transmitted by fiber optics to a visual monitor, resembling a TV screen, allowing the surgeon to see the interior of the joint and assess any injury or abnormality that is present.

Because space to work in the hip is limited, a special surgical table is used so that traction can be applied to that lower leg which increases the space in the hip joint. This makes visualizing pathology and performing the repair easier. The traction applied to the leg can result in a nerve injury, so special care must be taken when directing the placement of a post in the groin, which counters the traction forces, and in protecting the foot and ankle. The amount of time the traction is applied is monitored carefully to diminish risk of nerve injury. Fluid (typically normal saline) is instilled into the joint, which helps to distend the joint capsule and also facilitate visualization and performing a repair. Sometimes, in spite of these precautions, a nerve injury still occurs.

While some conditions are amenable to be repaired or corrected arthroscopically, conditions such as arthritis or congenital dysplasia historically have not been successfully treated with a hip scope. One of my strong impressions is that when a condition develops that could be treated arthroscopically, the sooner the conditions is corrected, the higher the probability of success. With time, the condition often worsens leading to cartilage damage and the development of arthritis. Advantages to hip arthroscopic surgery include:

• Much smaller incisions are made with less soft-tissue dissection than during an open surgical procedure to treat the same problem.

• It typically is performed as an outpatient procedure.

• It fosters earlier and accelerated rehab compared to an open procedure, although after arthroscopic surgery patients may be instructed not to bear weight on the operated leg for a period of time and to wear a hip brace to limit hip motion.

• For many patients, it allows them to return to normal activity faster than if a traditional, open-incision procedure is used.

• For some conditions, there is a higher incidence of success and a lessor chance of femoral head avascular necrosis (AVN) than if treated in an open fashion.

Who IS a candidate for hip arthroscopic surgery?

Treatment with hip arthroscopic surgery may be a consideration for the conditions I’ve listed below. There are other conditions, which can also be treated arthroscopically, that I did not mention.

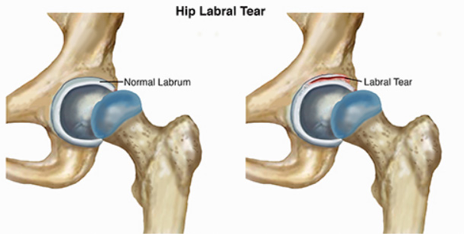

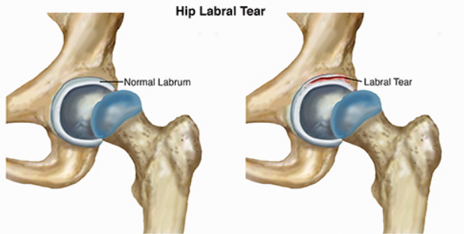

Labral Tear:

The labrum is a soft tissue structure with a rubbery consistency that is attached to the boney rim of the acetabulum. It functions like a gasket which overlies the cartilage covering the femoral head creating a suction, and helping to nurture the cartilage while providing stability. If a labrum tear occurs, it can cause mechanical symptoms such as locking, catching and pain. The symptoms can be episodic or constant. Typically, these symptoms occur with activity and pain often is related to specific joint positions. Arthroscopically, the tear can be repaired by removing the torn aspect of the labrum while leaving a stable rim of the remaining labrum. Preferably, the tear is repaired by suturing it together and / or reattaching it to the boney rim using bone anchors to try and preserve this important structure. Sometime this is not possible and the torn labrum must be removed to relieve symptoms.

More frequently, a labral tear occurs secondary to an underlying mechanical or congenital problem. In these cases, simply treating the torn labrum and not correcting the primary cause that lead to the tear will provide only temporary relief. This is because the underlying boney problem that led to the tear still is present.

Femoral Acetabular Impingement (FAI):

Imagine the boney rim of the socket bumping up against the side of the femoral head or neck. The labrum becomes trapped or compressed between the head and the socket and tears. For this condition to be treated successfully, not only must the labrum be repaired but the underlying boney abnormality causing the impingement must be corrected. Some people are born with abnormal hip anatomical structures but never develop symptoms. Those patients who are very active and often involved in sports appear to be more predisposed to becoming symptomatic.

There are three major types of FAI:

o Pincer impingement describes a condition where the boney rim of the socket extends beyond the normal rim. The labrum becomes crushed under this prominent rim. The arthroscopic surgeon must lift the labrum off of the abnormal boney rim. The excessive acetabular rim is reshaped using special burrs and tools to make it smaller and then the labrum is reattached.

o CAM impingement occurs when the femoral head is not round and cannot rotate smoothly inside of the acetabulum. A boney prominence or “bump” forms at the femoral head neck junction. Once again, the labrum and acetabular cartilage can be damaged as the head now grinds under the acetabular rim. In this case, the arthroscopic surgeon re-contours the femoral head by removing the “bump,” so the head will glide under the natural socket. If the labrum is torn, it is repaired as well.

o Combined pincher and CAM impingement is when both conditions are present and is the most common.

Loose Bodies:

This term refers to small pieces of cartilage and/or bone that break off and remain within the joint. They also are called “joint mice,” because they move around in the joint. Since cartilage does not have a blood supply but rather receives its nourishment from the synovial fluid, chondrocytes which cover these joint mice fragments can remain alive and even grow. These small, floating pieces can become caught in the hip during movement. This can make you feel as if your hip were locked or stuck and often results in sudden pain. Loose bodies often can be removed arthroscopically. Usually, more extensive problems are found within the joint when these are removed because they typically occur from past trauma.

Synovitis:

Synovium is the tissue which lines the inside capsule of our joints. It secretes synovial fluid which helps lubricate the joint and nurture the hyaline cartilage. When there is a problem within the joint, the synovial tissue becomes inflamed and more fluid is secreted (an effusion). This can cause pain. This synovial tissue can be debrided or partially removed arthroscopically to treat symptoms. Symptom relief will only be temporary unless the underlying cause for the synovitis is solved.

Snapping Hip Syndrome:

This is characterized by a snapping sensation and sometimes an audible popping noise when the hip is flexed and extended. There are several causes, but most common is when tendons or soft tissue catch on bone and then snap when the hip is moved. The offending tendon can be released or trimmed to relieve this. Usually by changing hip alignment and mechanics with physical therapy, this condition can be successfully treated without surgery.

Hip instability:

Hip-joint instability can develop secondarily to congenitally lax connective tissue or after trauma. Normally, the femoral head remains centered within the socket throughout hip motion by the boney confines of the acetabulum, the labrum and the surrounding hip joint capsule. If the surrounding hip joint capsule becomes attenuated or stretched out, or completely detaches from the rim of the socket, the ball can lift out of the acetabulum during motion. Patients report pain and a feeling of instability. Ultimately this abnormal movement will damage cartilage and result in arthritis. Arthroscopic techniques have been developed to tighten or plicate the capsule to help stabilize the joint, and also to reattach a detached capsule to acetabular bone.

Acetabular/pelvic fractures and periacetabular osteotomies (PAO):

Repairing acetabular and pelvic fractures and performing periacetabular osteotomies are major reconstructive surgeries requiring an open incision. Occasionally, hip arthroscopy will supplement the open reconstruction so intra-articular structures can be assessed and repaired with more precision.

Extra articular hip indications:

Structures located outside the hip joint capsule, including bursa or tendon attachments, also can be assessed and treated arthroscopically. For example, the iliopsoas tendon can be released from its insertion into the lessor trochanter and its bursa debrided.

Who is NOT a candidate for hip arthroscopy?

An individual who’s hip X-rays show arthritic changes such as narrowing of the joint space, peripheral bone spurs, or subchondral bone cysts are typically not good candidates, even when they are being treated for a condition which often can be helped arthroscopically. An MRI scan is often more sensitive in demonstrating subtle intra-articular pathology that can be treated arthroscopically, as well as early arthritis or cartilage damage. MRI scans with enhancing dyes reveal even more detail.

When cartilage delamination is observed (the acetabular hyaline cartilage is lifting off its boney bed, typically at the acetabular edge where it abuts the labrum), it is not a good prognostic indicator for a successful arthroscopic result. If a labrum is torn and not repaired, with time the probability of cartilage delamination increases.

That said, new techniques continue to be developed to treat cartilage loss or repair cartilage. In a prior blog article, I discussed a number of these innovative new techniques. Many have been developed and are continuing to be developed. Most have been studied more in the knee than the hip. Their applications in the hip are logical, but more difficult to apply.

Attempting to repair cartilage, particularly in the hip, has been inconsistent. Nothing in medicine is absolute and everything that we try has a risk-to-benefit ratio.

I look at it like this. For a very young person, who has better healing potential than an older person and hopefully a long life ahead, applying new techniques, even with a guarded chance of success, may still be reasonable. The hope is to salvage the joint, recognizing that if a technique fails, “no bridge has been burned” and a different procedure or even a hip replacement can be performed. In a middle-aged or older individual, when the chance of success of using one of these techniques is quite small, then their applications may not be reasonable and joint replacement could be the best choice. Of course, we all continue to re-define “young” and “old.”

As with any surgical joint procedure, there can be complications including infection and continued pain after surgery. A significant concern is with the key nerves and blood vessels that surround the joint. While nerve damage is uncommon, it is important to discuss your particular condition with your surgeon.

If an acute injury leads to a problem and it is treatable arthroscopically, then usually it is to the patient’s advantage to be treated sooner rather than delay the surgery. If a patient has hip dysplasia (on the X-ray, it looks like the femoral head is not fully covered by the socket or acetabulum) and a torn labrum, then hip arthroscopy alone typically will not solve the problem.

For a young person hoping to avoid a total hip replacement or some other procedure, arthroscopy might be a reasonable alternative. I encourage patients to educate themselves regarding the risks and probability of success.

Also, make sure you chose a surgeon who has performed a significant number of hip arthroscopic surgeries. Talk frankly with your doctor, not only about your surgical goals, but about his or her surgical success rates as well as the potential success rate for your particular problem.

We thank you for your readership. If you would like a personal consultation, please contact our office at 954-489-4575 or by email at LeoneCenter@Holy-cross.com.