Understanding Hip Fractures: How These Breaks Differ and Why Recovery Can Be Challenging

Worldwide, the number of hip fractures is expected to surpass six million by the year 2050. In the U.S., however, from 1996 to 2010 there was a decrease in hip fractures and while the reason for the decline has not been categorized definitively, lifestyle changes including more focus on vitamin D and calcium, avoiding smoking, moderating alcohol usage, more awareness of falling and regular exercise all could play a part.

Historically, hip fractures left patients crippled or even caused death due to lack of mobility and all its associated complications. Fortunately, this landscape is changing. Today, with the advances in prosthetics for hip replacement and hardware to repair fractures, not only have deaths been reduced, but people are getting back to active lifestyles.

In this blog post, I will discuss different types of hip fractures as well as the strategies for treating these difficult injuries. In a follow-up blog, I’ll discuss complications that sometimes occur with treatment of these fractures and what can be done to correct the problems and still deliver optimum results.

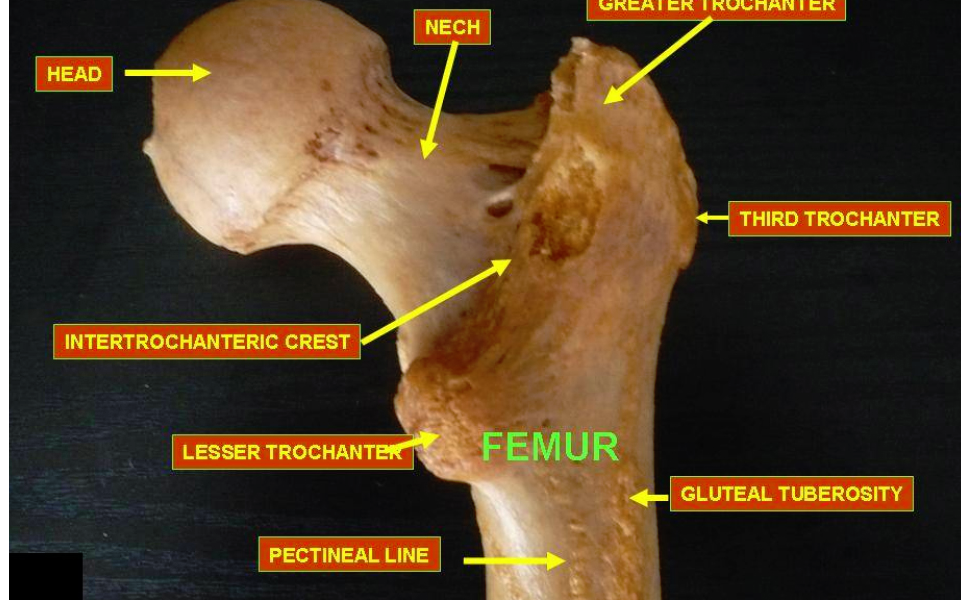

The “hip joint” refers to the socket, or acetabulum, which is the concave surface of the pelvis and the ball or femoral head that lives and moves within this socket. Fracturing or breaking a hip typically refers to a break occurring through the upper femur (thigh bone). Occasionally, trauma can result in the acetabulum or pelvis fracturing with or without the ball also dislocating. Technically, this also would be considered a hip fracture, although fortunately it occurs much less frequently. My remarks in this blog will be limited to the more-commonly occurring hip fractures that only involve the upper femur.

Hip fractures are characterized by where the fracture occurs: whether it occurs inside or outside the hip joint capsule. The hip joint capsule defines the true hip joint and is lined with synovial tissue, which secretes synovial fluid that helps lubricate the joint and nurture the hip’s supporting hyaline cartilage.

Intra-capsular fractures (fractures that occur inside the capsule) have a higher incidence of not healing and/or the femoral head losing its blood supply and later collapsing. Extra-capsular fractures (fractures that occur outside the capsule) tend to heal if the fracture is realigned or “reduced” and then stabilized with metal plates, screws or a rod, to maintain the reduced position and minimize movement at the fracture site, because this part of the skeleton has a much better blood supply and the bone is cloaked in muscle.

Femoral neck fractures are the most common type of intra-capsular break, especially in elderly people with osteoporosis, physiologically normal bone that has lost a significant amount of its mass or density. Osteoporosis is more common in woman so these fractures occur more commonly in women than men. The femoral neck is structurally the weakest part of the femur. Poor balance, side effects from medication, deteriorating eyesight and increased difficulty in mobilizing in various environments often lead to falls that result in fractures. As our population ages, more people well into their 80s and 90s who have osteoporosis become more vulnerable to these types of fractures

Occasionally, a patient with severe osteoporosis will present with acute hip pain that is increased with movement or weight bearing, but without a history of specific trauma. Plain X-rays may or may not demonstrate a fracture but an MRI does. These patients have insufficiency fractures – the bone was not sufficient to support the normal physiologic loads – and these too are becoming more frequent in elderly people with osteoporosis. Again, the femoral neck is the most common location for these fractures. Maintaining a high index of suspension is very important because a delay in diagnosis can lead to the fracture displacing and all the associated complications.

Young people without osteoporosis also can develop hip pain secondary to a stress fracture through the femoral neck. This injury typically occurs after excessive, repetitive-impact activities, classically seen after “forced marches” during Army boot camp or running. Once again, maintaining a high index of suspension is critical.

Extra-capsular fractures occur outside of the hip capsule. The intertrochanter region is an area of the femur just below the hip capsule and includes the greater trochanter, where the gluteus medius and minimus (hip extensors and abductors) attach, and the lessor trochanter where the iliopsoas (hip flexor and external rotator) attaches. When a fracture occurs through this area, it is referred to as an intertrochantic fracture or intertroch fracture. The area just below the trochanter is the subtrochanteric region and a fracture through this area is often referred to as a hip fracture. We call these fractures subtroch fractures, and often are combined with an intertroch component. It’s important to characterize the location of the fracture because treatment methods vary as well as the prognosis for healing and recovery.

It takes a vast amount of energy for a young person to break normal, healthy bone – some estimate as much as 1,700 pounds per square inch or more – compared with the significantly lesser amount of energy required to fracture osteoporotic bones. The direction that the energy takes as it enters and exits the bone, as well the position of the limb when the trauma occurs, results in the fracture pattern and the type and severity of the fraction. Despite the fracture patterns sometimes appearing the same in healthy, strong bone versus osteoporotic bone, it’s a very different injury because the energy and trauma needed to break healthy bone is so much greater. The increased energy also imparts significant injury to soft tissues that surround the bone and results in tissue tearing and bleeding. When caring for anyone with a fracture, the damage to the soft tissues as well as the bones must be considered and fully taken into account when planning the best treatment strategy.

When I care for a patient with a fractured hip, young or old, I always explain that the recovery is often more difficult than it is for someone who undergoes elective hip or knee surgery or replacement. This is due to the greater damage to the soft tissue and bone in a trauma patient compared with the elective hip or knee patient. While the hip fracture patient is an emergency, the elective patient can be optimized both mentally and physically prior to surgery. Also, the patient with a broken hip often has a more difficult rehabilitation after surgery. The broken bones and injured tissues must heal and frequently the fracture pattern dictates that the patient delay full weight bearing on the injured lower extremity until provisional healing has occurred.

If a femoral neck fracture is non-displaced or minimally displaced, then the decision might be to internally fix the fracture rather than to replace the hip, with the hope of saving the hip and avoiding a prosthetic. I then would insert two or three very thin pins (or guide wires) across the fracture site in a parallel fashion into the strongest or densest part of the femoral neck and head. These pins are inserted through tiny little incisions on the side of the hip. The exact placement is guided and confirmed by using a fluoroscope, which is a moving X-ray image. Over these little pins, I implant larger cannulated (hollow) screws and then remove the guide wires. The goal of this strategy is to salvage the hip rather than replace it with a prosthetic. This strategy is reasonable if the fracture is non-displaced or very minimally displaced and the patient did not have underlying symptomatic arthritis or hip disease prior to the fracture.

If the fractured neck is significantly displaced or the person has symptomatic arthritis, then replacing the hip with a prosthetic affords a much better chance of delivering the best result. In young people who sustain a displaced femoral neck fracture, a decision still might be made to attempt salvage the hip by reducing the fracture to improve the alignment as close to anatomic as possible, and then internally fixing it with the hope that it will heal. If it fails, at a later date the pins would be removed and an elective total hip replacement would be performed. The probability of this strategy failing is significant, but the decision may be made to go forward in spite of this to try and avoid a prosthesis.

If the decision is made to treat the fracture with endoprosthesis, the surgeon may choose a partial hip or total hip. If a partial hip is chosen, a stem is inserted into the upper femur and a prosthetic head is placed on the stem. The traditional endoprosthesis was the Austin Moore, where the ball and the stem are a single piece of metal (monoblock). This type of prosthesis no longer is used commonly in the U.S. Instead, a prosthetic ball is placed on the taper of the stem and the ball is placed within the patient’s native socket and articulates against the cartilage. This type of construct is called a monopolar endoprosthesis. A more commonly used construct to treat hip fractures in the US is a bipolar prosthesis. Now, the larger ball in implanted over a much smaller ball, which in turn is impacted on the hip stem. It’s referred to as bipolar because it moves in two planes – between the small and large balls – and between the large ball the patient’s own acetabular cartilage. Many surgeons feel this helps to protect the native cartilage.

If there is underlying hip pathology or arthritis (the acetabular cartilage is worn and compromised), then it might be best to perform a total hip replacement. Total hips produce the best and most consistent results because two prosthetic parts are moving against each other, rather than a prosthetic head against natural cartilage. Many surgeons, including me, will preferentially perform a total hip rather than a partial hip, even if the femoral neck fracture did not have pre-fracture hip symptoms or arthritis. I feel I consistently can deliver a more prefect result with a total hip; however, performing hip replacement surgery must be weighed against other concerns and possible complications. An advantage of the bipolar is that it has a lesser incidence of dislocation than the THR and this is an important consideration in a person who may be prone to falling.

If the fracture is extra-capsular then it almost always is better to design a treatment to promote fracture healing. The goals are to reduce the fracture to as close to an anatomic position as possible and then internally hold the fracture fragments in a fixed position until the fracture heals. With some fracture patterns, this can be extremely difficult to achieve. Fracture fragments must be reduced into a stable pattern so that compressive forces that occur across the fracture site result in the fragments compressing together, which stimulates healing without significant displacement. The pins used to fix a femoral neck fracture are placed parallel to allow a controlled subsidence or compression at the fracture site. Likewise, the hardware used to fix extra-capsular fractures is designed to promote controlled compression.

Intertroch and subtroch fractures are most commonly treated in the U.S. with a large hip screw placed across the neck and into the femoral head, and with an intramedually rod or nail placed down the femoral shaft. The hip screw slides through a hole in the upper part of the nail and allows for controlled subsidence. Prior to the development of these nails, the hip screw was placed through the barrel of a side plate, which was fixed to the femur with multiple screws. This type of device still is used and both devices have advantages and disadvantages. One of the main advantages of the nail with sliding hip screw is that it can be implanted through smaller incisions, often resulting in less bleeding compared with a side plate. One of the disadvantages of the nail is that it is placed through the tip of the greater trochanter, which can compromise the abductor mechanism. Recall that the gluteus medius and minimus insert into the greater trochanter, and it is often much more destructive when the nail must be removed.

No matter which device is used, the key is to achieve an excellent, stable fracture reduction. Sometimes, this actually requires opening the fracture site to improve the reduction and place additional screws or cables. It’s critical that the fracture fragments compress together through controlled subsidence. When a fracture is internally fixed, it becomes a race between the fracture healing and the hardware failing. If the fracture does not heal, then the hardware will fail by breaking or by “cutting out of the bone.”

As surgeons, we try to optimize the environment for healing by reducing the fracture fragments into a stable position and then holding that position with screws, plates, nails or cables. However, at the end of the day, our bodies must heal the fracture.

In my next blog I’ll discuss complications that can occur after hip fractures and what can be done to resolve them.

We thank you for your readership. If you would like a personal consultation, please contact our office at 954-489-4575 or by email at LeoneCenter@Holy-cross.com.

I am 65, have osteoporosis and after a bad fall and a fracture, my surgeon chose to use three pins to repair joint. I am now concerned after reading your blog that this was perhaps not the right choice. It has been four days since the surgery and a have little pain and I am getting around with a walker. What can I expect down the road. Can I build up bone mass?

Dear Linda,

When your surgeon decided to internally fix your fracture with screws rather than replace your hip, he or she did so with the hope that the fracture would heal and ultimately you would do well without a hip replacement. Many people who undergo this treatment do well and hopefully you will too.

At this point, the direction of treatment has been made, your surgery is done and you are doing well. Be optimistic for the future. Follow your surgeon’s recommendations regarding rehab. If in the future a problem develops or you are not doing well, then explore further.

The degree of osteoporosis that you’ve developed needs to be quantitated. Long-term recommendations and possible medicines can be prescribed if appropriate. For now, you should focus on rehab. Taking meds or food supplements almost certainly will not change the natural history regarding your hip fracture healing. Treatment of osteoporosis may, on the other hand, help prevent future fractures.

I wish you a full recovery.

Dr. William Leone

We thank you for your readership. If you would like a personal consultation, please contact our office at 954-489-4584 or by email at LeoneCenter@Holy-cross.com. General comments will be answered in as timely a manner as possible.

I am 44 yrs old and just had my a total hip replacement a week ago. After coming out of surgery I was informed I had a hairline fracture in the upper part of the femur. Apparently my bone was so strong it was hard to get the device in. Doc put cable around it and said only 40 lbs weight baring for 6 weeks on my right leg. I was so stressed and disappointed. I had my left hip replacement 1 year ago and fully owned my rehab walking in 3 weeks and caring for my infant. My little guy is now 20 months and I want a great quality of life to raise him. Doc mentioned something about trying to put the same hip in as the last one.

Dear Concerned,

It is not uncommon that a small fracture in the upper femur occurs during preparation or final impaction of the femoral component. It sounds like your surgeon recognized the fracture, told you about it, appropriately treated it with a circlage cable and instructed you to limit your full weight-bearing on that leg for a short period. Honestly, I think he or she did everything right. There is a very high probability that the fracture will heal, your stem will stabilize and in the long run this will be only a small bump in the road. You are hoping that your hips are pain free and last many, many years and there is no reason why this scenario still will not occur.

Hang in there. Keep the faith. Communicate with your surgeon. You can still do extremely well.

Sincerely,

Dr. William Leone

We thank you for your readership. If you would like a personal consultation, please contact our office at 954-489-4584 or by email at LeoneCenter@Holy-cross.com. General comments will be answered in as timely a manner as possible.